▻ Viva Argentina! – Part Three – Laura Catena

In conversation with Laura Catena

Episode Summary:-

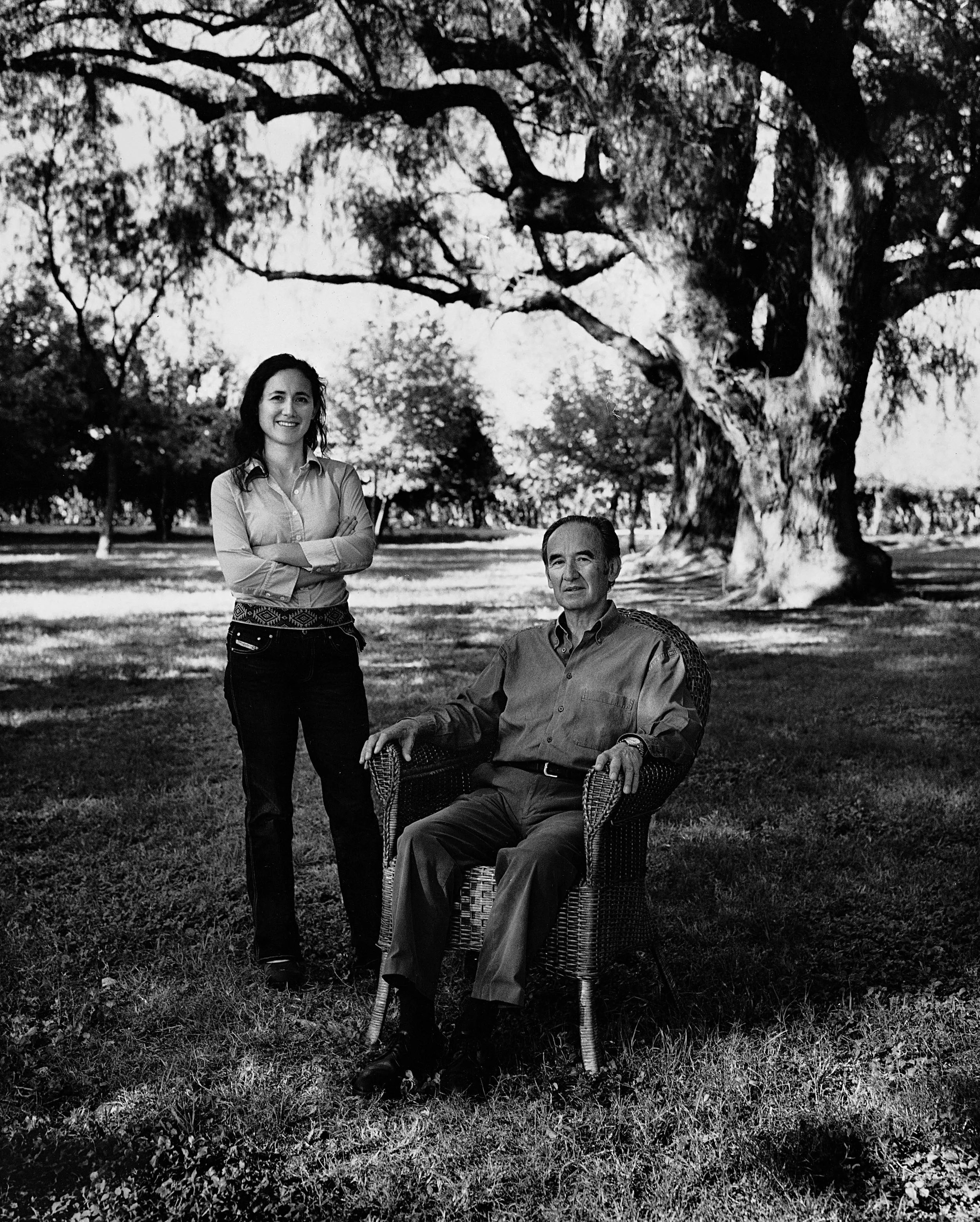

Nicolas Catena came to Argentina from Spain at the turn of the 20th Century, planted vineyards and established not only a winery, but a dynasty – four generations later, Bodega Catena Zapata is the oldest family-owned winery in the country, and a widely acknowledged leader in the pursuit of quality for Argentine wines. In this episode of Great Wine Lives, our U.S. editor, Elin McCoy, talks with Laura Catena, its managing director and a founder of the Catena Institute of Wine, an academic partnership with several universities devoted to rigorous research into viticulture and enology.

Elin begins by noting that Catena is one of the world’s best-known and admired wine brands, and synonymous with the rebirth of Malbec – “talking of their history is like talking of the history of Argentine wines,” she says. Introducing Laura Catena, Elin relates how she is the author of several books, director of the winery, travels the world talking about Catena and Argentine wine, has had a career as a medical doctor, and raised a family as well: an exemplar of creative energy.

Laura’s introduction to wine – which, she cautions, isn’t recommended now – was at about age five, when the children were allowed to eat with the adults at the family table: “We were allowed to have small glasses of Rosé.” Early on, she wanted to be a doctor, work to help people, and she succeeded in that, but also came to realize wine could be beneficial in many ways, from farming to the table.

Elin asks when she decided to join the family business, and how it came about. She says her father, Nicolas Catena, let his children choose: “He thought if they came on their own, they’d come with enthusiasm and joy.” When she did, he had her travel with him, wine-touring in France and California, to translate – she had attended U.S. universities – and help explain how he was trying to elevate Argentine wine. “He had met Robert Mondavi, who was beginning to challenge the French dominance in fine wine, and he used to say, we can compete!” When she was at university, he gave her an American Express card, had her buy Riedel glasses, and the best wines, to elevate her palate. Of course, she says, “I fell in love with wine, and worked with the family, little by little.”

““I fell in love with wine, and worked with the family, little by little.””

Elin asks what got her deeper into wine. She says she’d finished her residency, was a qualified doctor, when her father called her, announcing that The Wine Spectator had invited Catena to participate in The Wine Experience, their big show in New York – they’d be the first South American winery to do so. Her father thought it wouldn’t work, nobody in the family spoke good enough English, so she went.

“I’d see these long lines at the stands of Napa and French producers, but people would walk by our stand, see our name, and keep walking! The worst was when someone tasted the wine at the stand next to me, and spit it into my spittoon, and walked away!” She called her father and said this is impossible, we’re making great wine, but we have to convince people of that.

““Maybe it was the arrogance of youth, but I knew wine, I knew vineyards, I just had to know how to promote wine – that was something I had to learn.””

Elin asks if there are many other women in wine in Argentina now. Laura says when she became involved, it was mostly men, and in viticulture, entirely men; maybe there were some women in winemaking, working in the laboratories, but not in important jobs – and this was in the 1990s, not that long ago. But, perhaps because there are so many family wineries, there are more opportunities for women now, and responsibilities are more evenly split between men and women.

What sort of advice did her father give her, Elin wonders. Laura replies that he’s not a micro-manager, likes to get good people and let them run like a race-horse. When I said I didn’t know much about marketing, he said, “make a wine that’s better then the competition and sell it at a fair price, that’s it. . . It’s all about the wine.” So, she relates, we always tasted wine that cost twice as much as ours, from everywhere, as our benchmarks, and it worked. I’ve written books, travelled, done press campaigns, and social media, and I still can’t improve on my father’s system! He was always a great listener, she says. “I try too – my motto is, ‘hard on issues, soft on people.’”

On reflection, Laura says, one of the family’s guiding principles was to let you be your own person, and that has informed their vineyard practices and, ultimately, the wines. “it’s good parenting, and good business, especially wine – find what every vineyard expresses, not turning it into something else, based on soil, climate, cover crops, pruning, all of it, and it’s the same with employees and family members.”

Elin brings up the founding of the Catena Institute of Wine, a joint project with the University of California at Davis and the National University at Cuyo dedicated to research and development projects into viticulture and enology. Laura says it really got rolling in 1995, with the first extensive study of Malbec clones. “The selection wasn’t necessarily that good, so we also considered French cuttings, and considered aspects of our terroir as well. I wanted to do extensive research, to catch up with the knowledge of hundreds of years in France.”

Applying the research wasn’t always easy, she notes: “It was the time of the flying winemakers, coming in from elsewhere in the world, offering all sorts of opinions, like with canopy management, for example; they’d say, ‘take off leaves, let in sunlight,’ but at our higher altitudes, the grapes burned! And everybody wanted to make Malbec like Cabernet Sauvignon, but actually, Malbec from high altitudes should be made like Pinot Noir, because it has softer tannins--if you do long macerations, you lose the aromatics. We realized we had to do our own research, for our place and conditions, and that would be the key to making Argentine wines that were like the best of the rest of the world.”

Elin asks about high-altitude winemaking. Laura replies that of course it gets cooler as you go up, which enables retention of natural acidity. “For higher acidity and minerality (and thus beautiful age-ability) you go up or you go south, which in Argentina is also cooler, but also you get much less frost, more gravel and limestone, good drainage, and naturally lower yields. Also, you get thicker skins as the vine works to protect the grapes, so you get good tannins and more concentrated wines.”

Elin asks for some thoughts on Malbec in particular. Laura notes that when they started seriously exporting, people would often say all Malbec from Mendoza tastes the same, which she found disturbing and incorrect, a far too casual judgement. “There’s no such thing as New World/Old World geology, there are younger soils in some parts of Europe and older soils in some of the Americas.” She decided to concentrate on the larger aspect of terroir, enlisting the help of climatologists from UC Davis.

Elin homes in on this aspect: What was proved? Laura says that the combinations of soil and temperature differences in mountain vineyards can be proven chemically. Everybody knows the different terroirs of Burgundy, but they didn’t have hundreds of years showing that. “So we micro-vinified small batches, 24 wines from different parcels, different altitudes, even different latitudes north to south, all vilifications exactly the same, all Malbec, and analyzed the chemical composition over three years.” It was the first major study, and showed the distinctiveness of the profile of each. That, she declares triumphantly, is a definition of terroir!

““There’s no such thing as New World/Old World geology, there are younger soils in some parts of Europe and older soils in some of the Americas.””

Elin then moves on to age-ability, noting that most consumers don’t think about aging Argentine wine. Laura counters that they’ve researched that too, and found that mountain Malbec compares well with Cabernet Sauvignon. “Sometimes it’s more beautiful than Cabernet,” she says cheerfully. She thinks that, because Malbec tends to be smoother when young, people may think they won’t age well, that tannin is crucial, but that’s not necessarily so, as acidity is so important, and Argentine Malbec from the mountains has that: “We’ve done serious research, and found that the typicity of Malbec from the right terroir can remain for over five years.”

Elin asks about Bodags Caro, the Catena joint venture with Domaines Barons de Rothschild (Lafite). Her father had become known as the godfather of Argentine wine, she says, and he welcomed wine producers from all over the world and shared his knowledge with many who began their own ventures there. Some wanted to enter partnership with them, but they held off. Then they met with Baron Eric de Rothschild and Christophe Salin of Domaines Barons de Rothschild (Lafite). “They were very square with us, and we saw that we could combine our Malbec expertise with their Cabernet expertise; they were admirable, they didn’t come as conquerors, but to share.” The venture has been a success, she notes, and a happy experience. “Now I have the pleasure to work with Saskia de Rothschild, who cares deeply about the environment and her family legacy, and does it with such elegance.”

Laura discusses how the Catena Institute was also developed to use science to preserve nature and culture. “Preserving nature, I think, is really important, and with climate change it has become an emergency, and I’ve been an emergency physician so I understand the concept of emergency.” She is also concerned about culture: “wine is what we do in Mendoza”. She sees lots of threats to this, with companies wishing to mine in the area, as well as an ongoing water shortage. Water shortage is a major problem, and she is looking further north and south at vineyards. “If you want to survive as a wine producer in Argentina, you may need to move your production, and that’s quite scary.”

Another experiment has been natural wine and the Criolla grape. Criolla was bought into Argentina 400 years ago by the Jesuits, and the vineyards, which are in the east, have been grubbed up. She found that when experimenting with Criolla, that it performed better with no sulphur. She hopes that she can help economically revive the eastern region by promoting the new line of wines.

““My one wish is that every collector’s cellar has a section on Argentine wine, not Catena, Argentine wine.””

Elin is curious as to what success looks like to Laura. “My one wish is that every collector’s cellar has a section on Argentine wine, not Catena, Argentine wine.” She reiterates that people don’t think that Argentine wine can age because they haven’t tried them, and she confesses that even Catena didn’t keep enough library vintages to begin with.

One of the wine world’s problems is retaining people to work in the vineyards. At Catena Zapata she reveals that any person who works for the company and wants to advance their responsibilities is supported in further education. It is part of their family’s culture: “It’s not just about books, it should be about skills.” She has developed a programme to bring children to the vineyard and winery so they can see what an interesting job working in wine is.

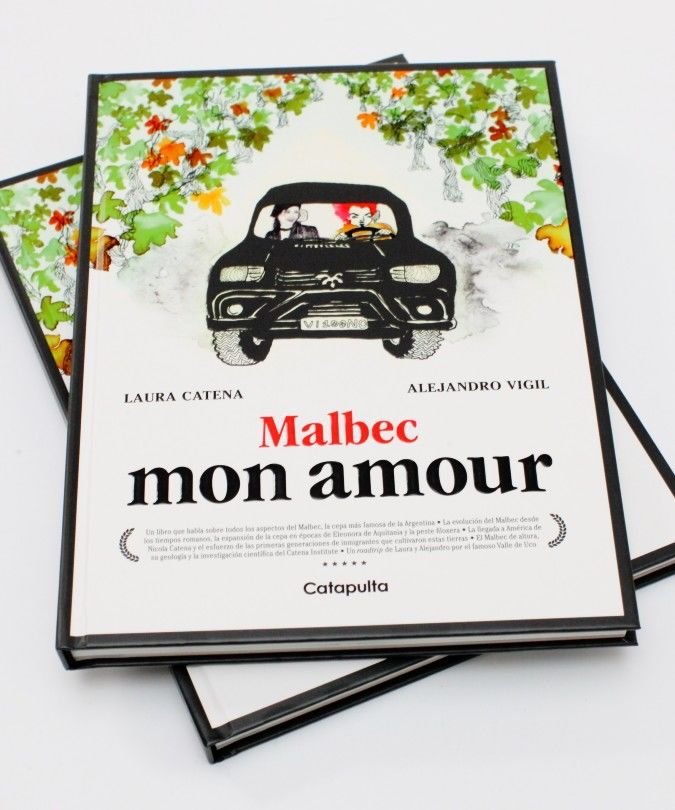

Apart from running Catena Zapata, she has her own project, Luca Winery, which specialises in old-vine vineyards and buys grapes from small producers; “50 percent of producers in Argentina own less than 10 hectares,” she notes. She wanted the freedom to access these vineyards and highlight the treasures within. “People think Malbec is a fashion, but it’s a variety which has been around for 2,000 years”. In her book, “Malbec Mon Amour,” which she co-wrote with winemaker Alejandro Vigil, she describes its history and how Eleanor of Aquitaine drank it and how it thrived in Bordeaux until phylloxera arrived. In the 1960s and 1970s in Argentina, 80 percent of Malbec was grubbed up, as people were looking for high-yielding grapes, and says it was her father’s decision to produce a high-premium fine Malbec that helped save the variety.

She concludes by talking about her successes and failures. “To me, mistakes are a blessing” which she sees as a learning opportunity. This is a wonderful moment for wine, she feels, with producers turning away from international styles and trying to make authentic wines from their regions.

Running Order:-

-

0.00 – 21.29

“Talking of Catena’s history is like talking of the history of Argentina’s wines” – Elin McCoy

– Laura Catena talks about her childhood with Elin McCoy.

– How while training as a doctor she became interested in the family business.

– Laura travels to France with her father and falls in love with wine.

– Laura discusses her father’s contribution to the wine world. -

21.30 – 34.54

“I wanted to do extensive research, to catch up with the knowledge of hundreds of years in France.” – Laura Catena

– Laura discusses founding the Catena Institute of wine.

– Making Malbec like Pinot Noir, not Cabernet Sauvignon.

– High altitude viticulture.

– The largest terroir project ever undertaken by the Institute.

– The age ability of Malbec and her desire to have Argentina’s wines in collectors’ cellars. -

34.55 – 01.07

“Preserving nature, I think, is really important, and with climate change it has become an emergency, and I’ve been an emergency physician so I understand the concept of emergency.” – Laura Catena

– How the joint venture between Catena Zapata and Domaines Barons de Rothschild (Lafite) came about to create Bodega Caro.

– Natural wine and the Criolla grape.

– Laura’s own project, Luca Winery, specialising in old vine wines.

– Her book Malbec, Mon Amour written with Alejandro Vigil.

– The history of Malbec from France to Argentina.

– Laura’s hopes for the future.

RELATED POSTS

Keep up with our adventures in wine

Sebastian Zuccardi is one of South America’s most dynamic winemakers. Sarah Kemp meets up with him to taste his new vintages and finds out from him the four new revolutions happening in Argentina’s vineyards.